Drawings

Noise Makers

Vermont

Music and Song Books

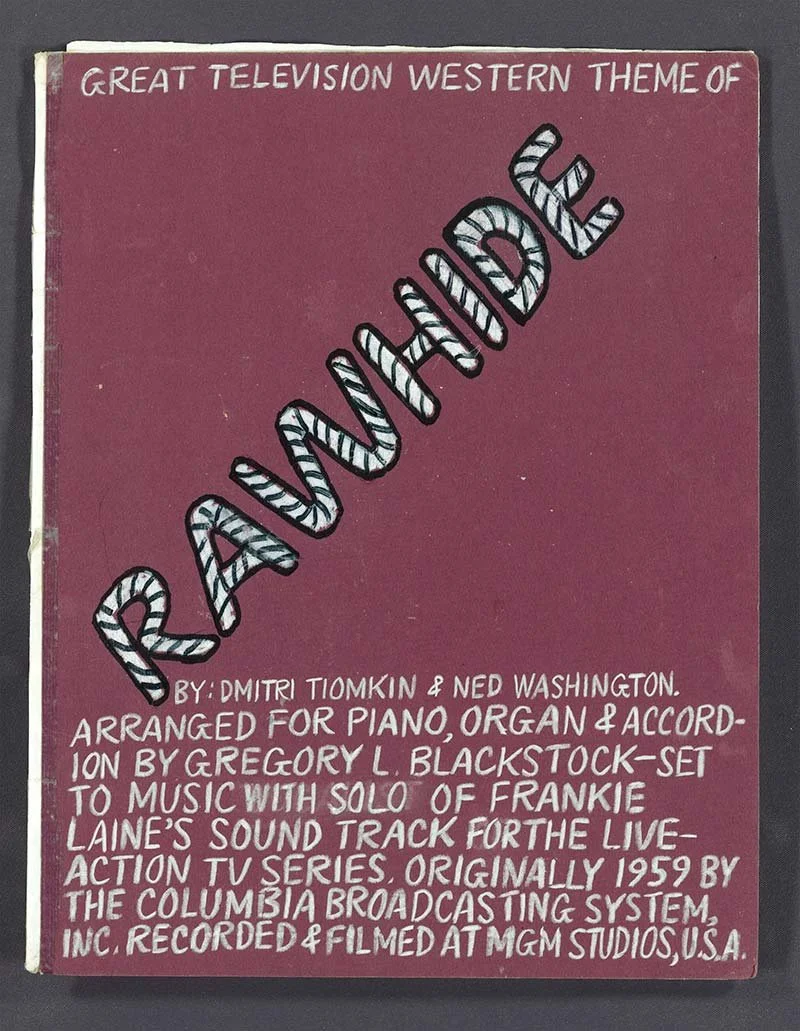

For decades, Gregory Blackstock has been creating these delightful re-workings of familiar and beloved songs, entirely for his own enjoyment. As an autistic savant, he relies on his prodigious memory of songs heard at the roller rink in his early childhood, learned from records and television, or referenced from his printed accordion music. He reviews the song in his head, before effortlessly changing it to a favorite key, usually a more difficult one.

Blackstock draws the staff, working freehand, with a ruler, or tracing over a copied blank staff, and then adds all musical notations by hand. If the melody has words, no matter how obscure, he will include all verses in precise handwriting. In creating a cover for the music, he exercises his visual creativity, providing relevant information about the song in text or image. Blackstock draws his covers with colored pencils and ink over colored construction papers, sometimes collaging photographs as illustrations.

Prints

The Incomplete Historical World,

Editioned Prints, Parts I, II & III

The Incomplete Historical World, Part I

The Incomplete Historical World, Part II

The Incomplete Historical World, Part III

About

Exhibitions

-

1946 - 2023

Seattle artist ,Gregory Blackstock, began drawing regularly in his mid-40s, cataloguing the world around him just as a botanist might classify plants in terms of families, species and genus, or an entomologist might arrange the various types of bugs within his collection. Blackstock is autistic, and his need to make sense of an unpredictable world is given a deeply satisfying outlet in his art. For him, the world is made up of things which need to be identified, ordered, and arranged - be they bugs, birds, vehicles or landmarks. One thing or another is seemingly of no greater weight but, once he decides to draw the subject, he seeks to reveal all of the specific variations within that subject.

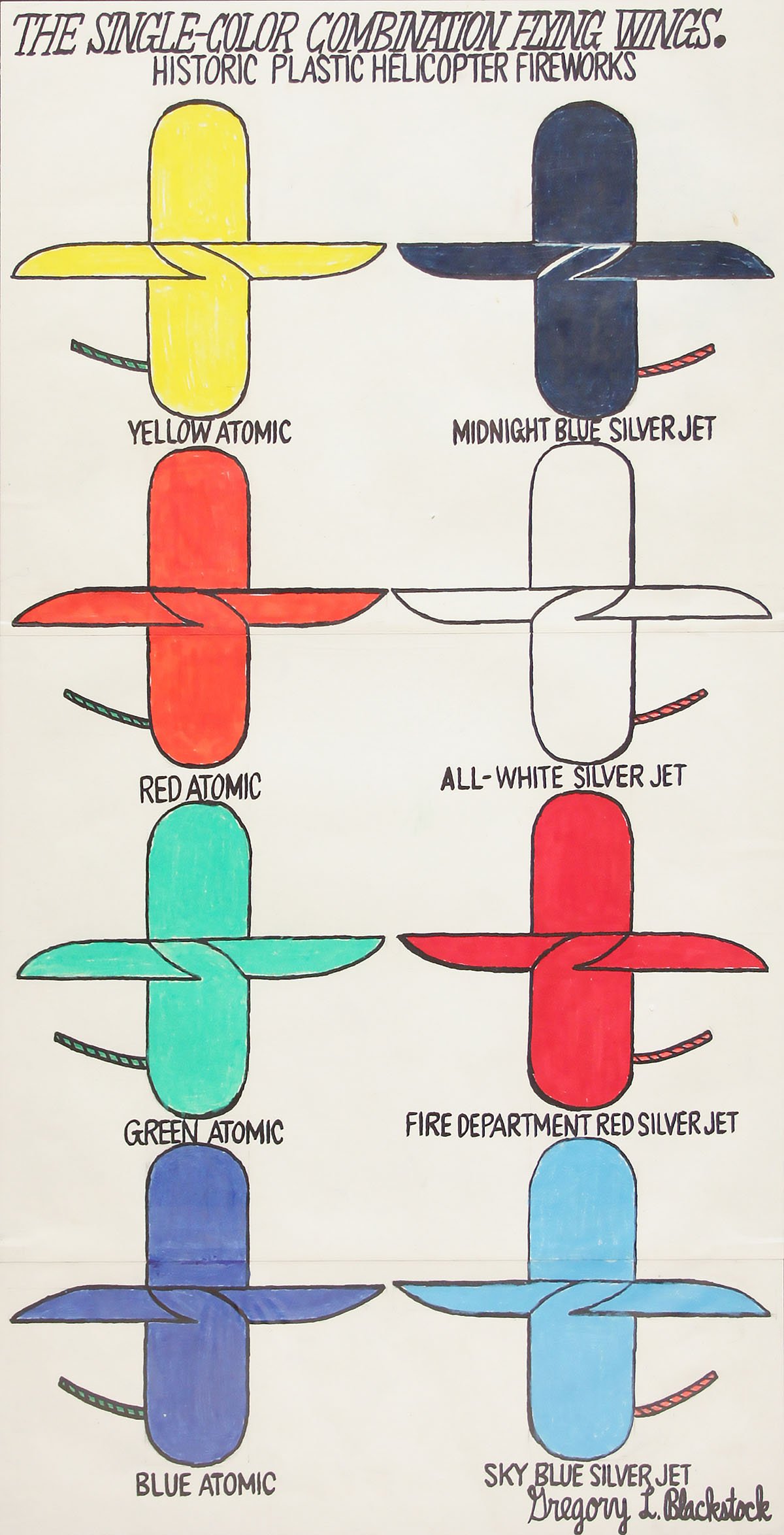

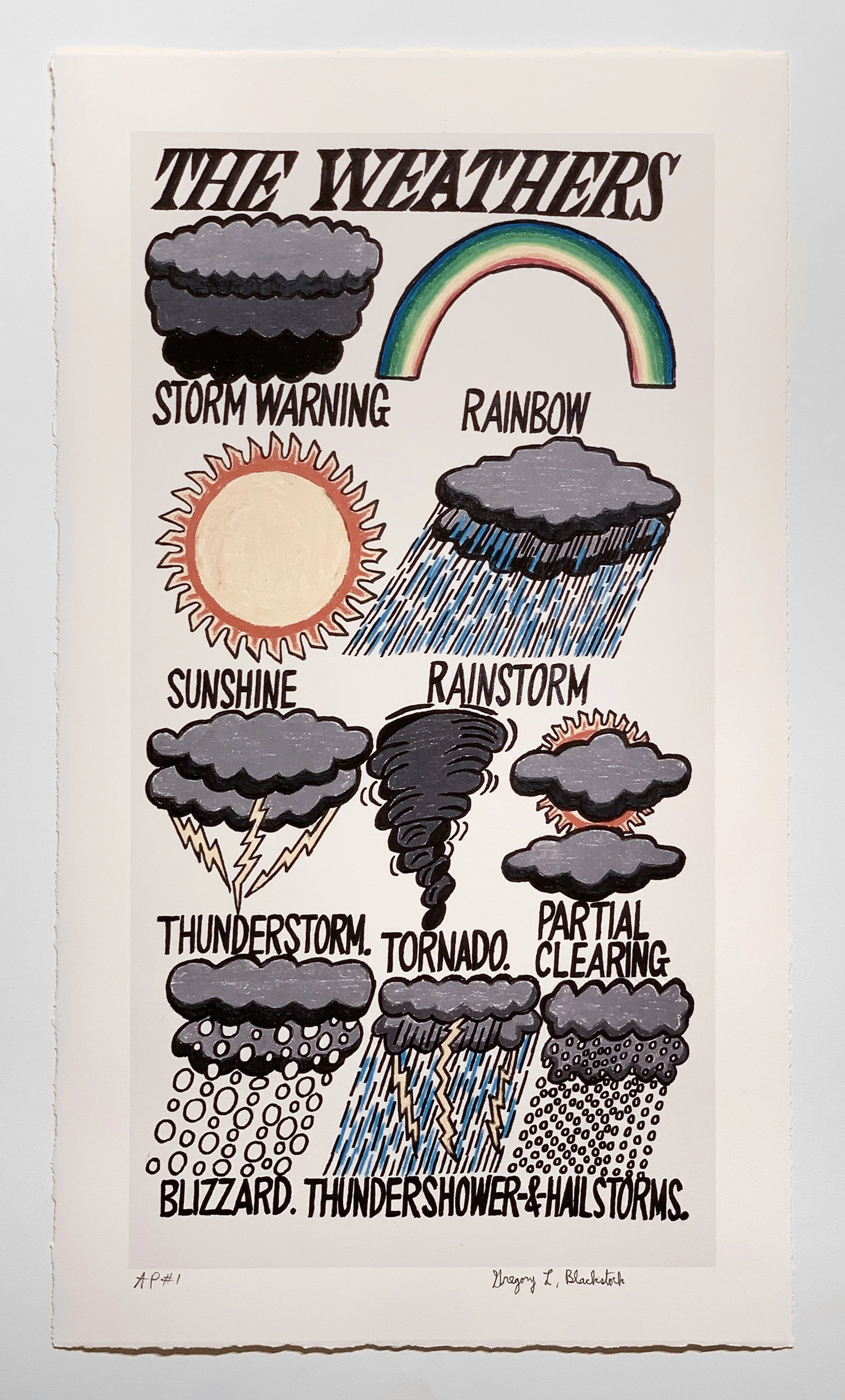

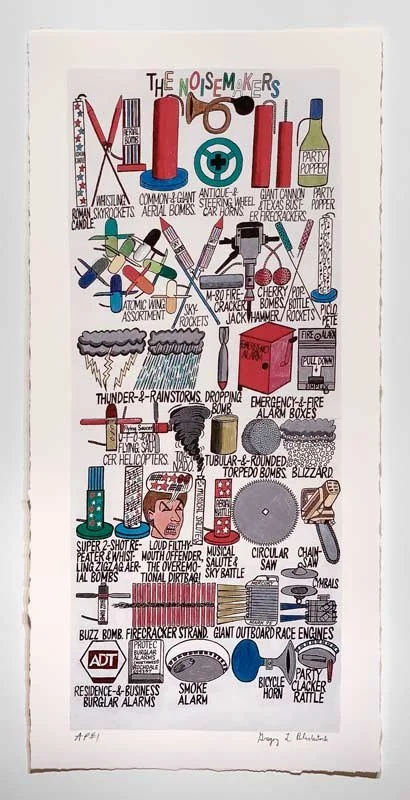

As he draws, he further breaks down those categorical distinctions, setting them on paper in neat rows and columns and always clearly labeling each item. He might create a simple, small drawing comparing two colors of The Tasmanian Devils, detail each one of The Great Americas Jays, or explore delightful variety in The Christmas Novelties. Occasionally, he will add informative or dramatic descriptors as well. His Notorious Harmful- to- Man Plants warns "irrigationists, farmers, linemen, foresters, campers, hikers, ranchers" in a lengthy caution about the dangers of poison ivy. While nothing is either too exotic or too banal to capture his attention, Blackstock particularly likes to depict things that are dangerous, irritating, or loud.

TECHNIQUE

Blackstock's work showed remarkable power and precision from the start, as if he had been storing data in his memory banks all his life. His uncanny depictions are drawn with incredible precision and a vivid use of color. Straight lines, musical notes and text, are all executed freehand. The detail to his work, aided by his innate memory skill, is nearly faultless.

For his research, Blackstock buys books, visits libraries and, when possible, studies the subject itself. He cannot use a computer and often leaves it to the helpful librarian to select an image from a computer search and mail it to him. He learns incredibly detailed information about each of his subjects, memorizing a range of geographical, anecdotal, and scientific information he will never forget.

The artist does not strive to make the drawing realistic but it must be factually correct. He is not drawing as a photorealist; he's drawing as a lover of information. First and foremost, he must be able to NAME what he is drawing, and it not only has to be specific (pine tree vs. maple tree), but it has to be exact (Ponderosa Pine vs. Western White Pine) and he is careful to draw it in a readable fashion. It also bothers him if for some reason he leaves out any example of his chosen category. Occasionally, the omissions from one drawing will become the genesis of a second iteration which then completes the category to his satisfaction.

He begins by drawing the item in pencil, carefully labeling it, then outlining in black marker, and finally using colored pencil or crayon to fill in. He usually finishes one entire row in full detail before moving on to the next. As an artist Blackstock intuitively understands how he wants the subjects to fit on the page, with the total pattern of shape and color captured in his mind, before he even begins the piece.

Blackstock will usually have between 5 and 10 drawings in various stages of completeness at any given time. The more complex the subject, the more often he has to take breaks from it. Sometimes a year or more will pass before he is satisfied that it is finished. Other times, if an idea captures him, he will work steadily for hours and hours each day until the drawing is finished.

Paradoxically, while minute details of the subjects are a fixation for him, he is less concerned with the specific conditions of the physical drawing itself. Blackstock will add paper to the work to build it to a size he needs, regardless of whether it is the same tone or weight as the rest of the piece. He will often eat meals while he draws. If he bumps into or crinkles one of the drawings as they are casually stacked in his small apartment he makes no effort to repair it. Smudges, food stains, dimples, and rips are not important in his concept of getting a drawing right. He is also inclined toward an economy of material, holding on to paper from various sources, until he can make use of it in a drawing.

Although in 1966 the Seattle Times published one of Blackstock's earliest drawings, taken from the TV series "Batman," it wasn't until the late 1980s that he began to draw in earnest. While he clearly draws for his own satisfaction, he was thrilled when, working as a pot-and-dish washer at the Washington Athletic Club, the employee newsletter began to include small reproductions of his work in "Blackstock's Corner." He began to enthusiastically plan out his drawings based on the publication schedule with subjects ranging from state birds to state prisons, gardening tools to WWII bombers, and from mackerels to Boeing jet liners. He would solicit ideas from his co-workers, and sometimes credit them under the title. As the newsletter could reproduce his images only in black and white, Greg didn't regularly use color in his drawings until there was a new audience in the form of gallery attendees.

After he introduced color to his drawings in 2004, his categories became narrower and more specific while including even more color variations. For instance, in black and white, he might do a grouping such as The Herding Dogs. After color, he had to do a single drawing of all the possible colors of The Bearded Collies, another of the different shades of The German Shepherd Police Dogs.

HISTORY

Blackstock was born in Seattle in early 1946, long before the term autism was widely known. Although his parents were educated and relatively affluent, they could do little to nurture and support his unique needs, having no idea of what made him so different from other children. His family physician gave the diagnosis of paranoid schizophrenia (a common psychiatric label for the times) and Blackstock was sent to special boarding schools for "troubled" children in California from the age of 10 until he was 14. His father left the family home when Blackstock was about 11, further disrupting his difficult young life.

Because of his remarkable abilities in art, music, language and memory, Blackstock is now considered a rare "prodigious savant" according to Dr. Darold Treffert, the acknowledged expert on the subject, who has included the artist in his latest book, Islands of Genius. Blackstock exhibits many of the classic contradictions of the savant. Social conversations are very difficult for him, yet he can speak and understand the rudiments of about twelve languages, including Japanese, Mandarin Chinese, German, Tagalog and Czech. He obsessively reads and memorizes the thesaurus to improve his vocabulary, but he cannot understand which words are in current usage and which are archaic, nor can he grasp nuance or irony, find meaning in metaphors, euphemisms, or satire, all of which are the underpinnings of everyday conversation. It is difficult for Blackstock to interpret (human) facial expressions to gauge the mood of another person, and he cannot use empathy to imagine what that person is thinking. Therefore, though eager to engage with people, his interactions can be lengthy monologues about his own current interests.

Blackstock enjoys music, plays an enthusiastic accordion, and is self-taught on the piano and organ. He often relaxes by creating, from memory, hand-drawn sheet music of old favorites, while effortlessly changing them into a more difficult key. He fashions an artistic folder for each, then places it on the growing stack in his closet. He has no need to look at them again to remember how to play (and sing) all the verses of the music in its new key. He used to regularly frequent Seattle area sports arenas and the opera house to play his accordion outside as fans entered and exited. Even in his late 60's he can still be seen playing "The Husky Fight Song" near the entrance to the college stadium.

For Blackstock, rules and facts are his reality. What he learned as a child is immutable, and he takes comfort in the unchanging facts of the natural world. He is confused by the emotions of others, oblivious to the shifting tides of political correctness, and unnerved by advances in technology. He can expertly shade a drawing of a Goldfinch's wing, yet cannot understand verbal directions to "put the yellow plug into the yellow circle" when setting up a DVD player.

Gregory Blackstock worked most of his adult life. From a teenaged newspaper carrier, to his twenty-five years as a dishwasher at the Washington Athletic Club, he has rarely been idle. In the years since full retirement, he now spends many hours each day creating the drawings that catalogue the world for him.

EXHIBITIONS AND COLLECTIONS

In the years since his first exhibition in Seattle at Garde Rail Gallery in 2004, Blackstock's distinctive drawings have captured the imagination of art collectors throughout the world. A 2006 book of his works, Blackstock's Collections, (with introduction by Karen Light-Piña and foreword Dr. Darold Treffert) is now in libraries worldwide. Six of his illustrations were featured on a collection of limited edition men's clothing by the avant-garde French fashion label "Commes des Garçons," and the Seattle Art Museum Gift Shop has produced a t-shirt using his drawing of "The Art Supplies."

Garde Rail Gallery (now in Austin, TX) has shown Blackstock's drawings at the Outsider Art Fair in New York City, Aqua Art Fair in Miami, and Santa Fe's Outsider and Folk Art Fair. Blackstock's art has also been shown at the John Michael Kohler Art Center, Sheboygan, WI.

In 2011, the prestigious Collection de l'Art Brut in Lausanne, Switzerland presented a solo exhibition of Blackstock's work. Today, 18 of his works now reside in their permanent collection. In collaboration with award winning filmmaker, Philippe Lespinasse, the museum also produced a documentary about him, Gregory Blackstock, l'Encyclopédiste, that has been shown at film festivals in Montreal and Nice. Galerie Susi Brunner in Zurich, and Galerie Gugging in Vienna showed Blackstock's work in 2012.

Both Microsoft Corporation and the Seattle Art Museum own examples of the artist's work in their permanent collections. As well as Blanton Museum of Art, University of Texas at Austin, Austin, Texas and Collection de l'Art Brut, Lausanne, Switzerland.

Gregory Blackstock is exclusively represented by Greg Kucera Gallery, Seattle, WA. He is assisted in his life and daily endeavors by his cousin, Dorothy Frisch.

-

The following videos show Greg Kucera discussing Gregory Blackstock prints from THE INCOMPLETE HISTORICAL WORLD, PART I

THE AUTOMOBILE CLASSICS - COLOR

THE GREAT AMERICAN ART MUSEUMS

THE HISTORIC WORLD STRONGHOLDS

THE MAJOR WORLD TROUBLEMAKER BEETLES

-

by Dorothy Frisch

June 2021The question most often asked artist Gregory Blackstock is, “How do you choose what to draw?” A logical question as the artist has drawn nearly 400 individual subjects, ranging from accordions to World War II planes. Blackstock’s usual response is to shrug and say simply, “from my own head.”

While he has always had a prodigious memory for detail, the ability for self-reflection and accurate historical reporting are very difficult for this autistic man. Therefore, understanding the genesis of many of his artistic “lists” requires a bit of archeological sleuthing of his past.

Observation of his process leads us to understand that the foundations of a Blackstock drawing likely include attraction, memories, research, lists, and repetition. While attraction and memory play a large part in his selection of subject, he is relentless in his research (via librarians and books) in order to make a “complete” representation of his topic. As he researches, he makes lists, often dividing into subsets. Sometimes he creates but a single shape, with the colorations making up the subset. The colors themselves are meaningful to him, and he uses the official Crayola color names as unequivocal fact.

Music:

Blackstock’s father played the accordion and bought his son an instrument and enrolled him in lessons when he was still quite young. He easily learned to read music and did well with the repetitive nature of understanding an instrument, and it was an added bonus that he has near perfect pitch. He continued these lessons even when, as a young adolescent, he was sent away from home to a special school in California. His preferred instrument was made by Petosa, a celebrated local accordion maker. As a youngster, Blackstock would often go to the roller rink and he especially enjoyed the popular songs blaring over the loudspeaker. Decades later, he could still recall his favorites and created his own sheet music for dozens of these songs – usually changing the key and drawing colorful covers for them.

Things that Make Noise:

The senior Blackstock also nurtured the young boy’s love of racing boats and fireworks, both subjects making frequent appearances on paper. He spent many hours in “the pits” getting to know hydroplane drivers and was in thrall when the engines tuned up with their mighty roars. When in California, his aunt and uncle often took him to the airport to watch the planes take off and land, and he learned to mimic the exact sounds the different engines made. His older brother was a history buff and introduced the artist to books and models of WWII airplanes. Learning about war planes from various countries remained a lifelong interest. He greatly enjoys looking at his completed works, repeating aloud facts, sound effects, and the origin stories from his past.

Life Sciences:

A letter dated 1958 to his parents from the director of the “camp” where the twelve-year old Blackstock was then living, had this to say: “Greg spends a great deal of his free time studying life science books such as material on reptiles, insects, trees, flowers and birds. These books have been very stimulating and he is constantly seeking information concerning the subject matter. Many of the books have been completely memorized…” After his return home, he wanted to build on his introduction to gardening, which was a camp activity, and he created a small garden in his mother’s yard. He became a reader of seed catalogues and experienced the ruinous effects of cabbage moths and other garden pests. He later gave up gardening, but still loves studying the colors and varieties of vegetables and flowers, as well as further investigating those garden troublemakers.

Things that are dangerous:

Blackstock has been a devotee of the early television programs “Wild Kingdom” and Disney wildlife documentaries. He has entire sections of dialogue memorized and happily re-watches threadbare VHS copies he made from them. He especially loves the ones about the most dangerous of the big cats and bears, and has perfected the ferocious roars they make, often to the distress of his seatmates on public transportation!

Language arts:

At nearly 15 years old, a “progress report” from the second boarding school he attended praised his knowledge of grammar, vocabulary and paragraph construction, as well as his regular use of the dictionary and encyclopedia. Yet the school put Blackstock’s reading at fourth grade level. Reading comprehension tests are (were) difficult for autistic persons who do not understand figures of speech such as idiom, simile, irony, euphemism, or internalize shared experience. This is likely how he developed a fascination with the thesaurus, which offered multiple alternatives for words, yet this could not overcome his struggle with nuance, context, and significance. At some point he began creating personal “lists” of synonyms and would add his own interpretations of words or phrases which might belong. On the other hand, he found learning other languages quite easy. The director of this boarding school spoke German and offered to teach the language to Blackstock, who became nearly fluent in the two years he lived there. His instructor might have been surprised to learn that the teen would go on to learn, on his own, the basics of many other languages, including Czech and Mandarin.

Other Attractions:

In the early 1970s, Blackstock was working as a janitor at a large hotel near the airport. He became fascinated with the various tools in the maintenance room and began sketching them as a group when at home. The resulting drawing, labeled simply “Tools” was the first known taxonomic drawing he created and he was eager to present it to his mother, a portrait artist, when she returned from a lengthy trip. She expressed delight, but told him it was “too big.” Some years later he began again, creating drawings which were smaller, generally focusing on the subset of tools, such as The Trowels, The Housekeeping Tools, The Wrenches. He returned to the original theme in 2001 and produced The Miscellaneous Tools.

An Invitation:

As you enjoy the vast variety in the work by this remarkable man, we invite you to discover a little bit of Gregory Blackstock’s life as revealed in his art.

-

ONE PERSON EXHIBITIONS

2020

Solo booth in Outsider Art Fair, New York2018

Survey of Drawings, Greg Kucera Gallery, Seattle (2015, 2013, 2012)2016

Washington Athletic Club, Seattle, WA2012

Recent Works on Paper, Greg Kucera Gallery, Seattle2011 - 2012

Blackstock, Collection de l'Art Brut, Lausanne, Switzerland2008 - 2009

Gregory Blackstock, Garde Rail Gallery, Seattle, WA 2008 Vernacular Photography of Gregory Blackstock, Garde Rail Gallery, Seattle, WA2007

Gregory Blackstock, Garde Rail Gallery, Seattle, WA2006

Gregory Blackstock's Collections, Garde Rail Gallery, Seattle, WA2005

Gregory Blackstock, Garde Rail Gallery, Seattle, WA2004

Gregory Blackstock: Outsider Artist, Garde Rail Gallery, Seattle, WASELECTED GROUP EXHIBITIONS

2023

Day Jobs Blanton Museum of Art, Austin, Texas, Curated by Veronica Roberts with Lynne Maphies2013

Véhicules, Collection de l'Art Brut, Lausanne, Switzerland Outsiderism, Fleisher/Ollman Gallery2012

The Dream of Flying, Galerie Gugging, Maria Gugging, Austria Paul Amar, Gregory Blackstock and Gérard Rigot, Galerie Susi Brunner, Zurich, Switzerland2011

Hiding Places: Memory in the Arts, John Michael Kohler Art Center, Sheboygan, WI2010

Umbrella for the Arts: 40 Years of Bumbershoot Artwork, Seattle City Hall2009

Collected Fragments, Tyne & Wear Archives, Sunderland Museum & Winter Gardens, Sunderland, Great Britain Heroes for Autism, Avalon Hollywood, Los Angeles, CA Outside The Lines, Kirkland Art Center, Kirkland, WA2008

First Annual World Autism Awareness Day Exhibit, United Nations, Secretariat Building, New York, NY Don't 'dis' the Ability, Manhattan Children's Center, New York, NY2007

Windows of Genius: Artwork of the Prodigious Savant, Windhover Center for the Arts, Children's Museum, Fond-du-lac, WI2005

Four x Northwest, Garde Rail Gallery, Seattle, WASELECTED COLLECTIONS

Blanton Museum of Art, University of Texas at Austin, Austin, Texas Collection de l'Art Brut, Lausanne, Switzerland Hallie Ford Museum of Art, Willamette University, Salem, OR Seattle Art Museum, Seattle, WA Microsoft Corporate Art Collection, Redmond, WA Capital Group Corporate Art Collection

PUBLICATIONS

Einstein's Watch, Profile Books, 2009

LA Times Magazine, 2009

Holland Diep Magazine, 2009

Folk Art Magazine, 2007

BOMB Magazine, 2007

Blackstock's Collections, Princeton Architectural Press, 2007

Cover art for Autism and Talent, Oxford University Press, 2010

Le Potential Inexploité des Autistes, Hémisphères magazineFILM

Gregory Blackstock: L'Encyclopediste, documentary by Philippe Lespinasse, 2011

Savants, documentary for German television, 2008

Evening Magazine, KING-5 TV, Seattle, 2008

Rare Visions/Roadside Revelations, Kansas City Public Television, 2006OTHER HONORS AND AWARDS

2017

Wynn Newhouse Foundation Award2011

Artist Residency, John Michael Kohler Art Center, Sheboygan, WI2010

Award for Bumbershoot Arts Festival Poster, Seattle Arts Commission2008

Spring/Summer ready to wear menswear collection, Comme des Garcons, ParisBOOK SIGNINGS

2010

Shakespeare & Co. Paris France2008

Seattle Art Museum Shop, Seattle, WA American Museum of Folk Art, NY Outsider Art Fair, NY Princeton Architectural Press, NY -

Cascade PBS (formerly Crosscut)

ArtSEA: New animated film illustrates a beloved Seattle "outsider artist"

By Brangien Davis

July 15, 2021The Seattle Times

Seattle artist Gregory Blackstock's possibly last show with new work on view at Greg Kucera Gallery

By Melissa Hellmann

June 30, 2021Wynn Newhouse Awards

2017 Award Winner, Gregory BlackstockSeattle Times

Gregory Blackstock's intricate world is a charming one, too

By Robert Ayers

December 14, 2012

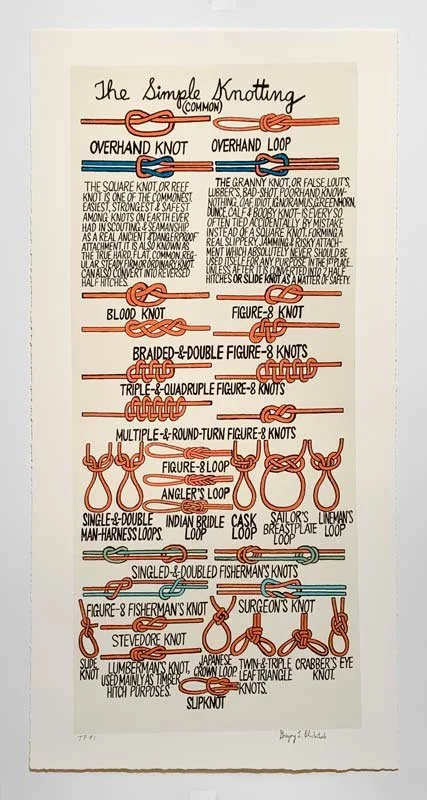

Graphite, colored crayon and permanent marker on paper

47 x 17 inches

$8,500