|

click to enlarge any image:

|

|

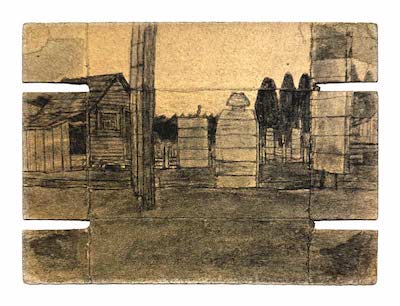

UNTITLED (2 houses / many small houses), date unknown

Soot and saliva on found board, double-sided

8 x 17 inches

$18,000

|

The reverse side

click to enlarge any image |

|

|

UNTITLED (bedroom, clothes / bedroom, chair on bed / shaped), date unknown

Soot and saliva on found board, double-sided

10 x 16 inches

$18,000

|

The reverse side

click to enlarge any image |

|

|

UNTITLED (house from front / back of house), date unknown

Soot and saliva on found board, double-sided

8.5 x 17 inches

$18,000

|

The reverse side

click to enlarge any image |

|

|

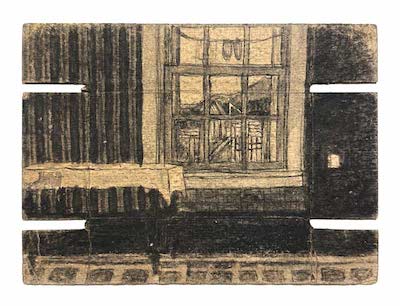

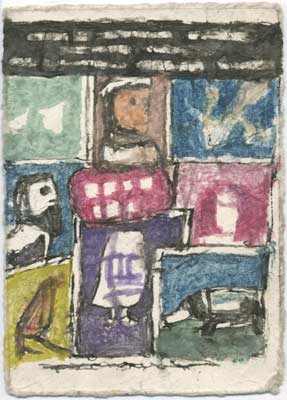

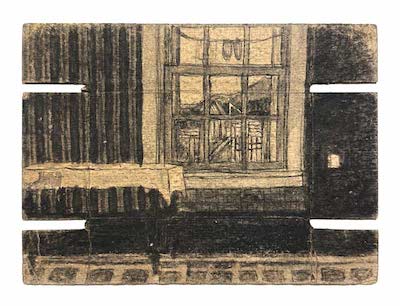

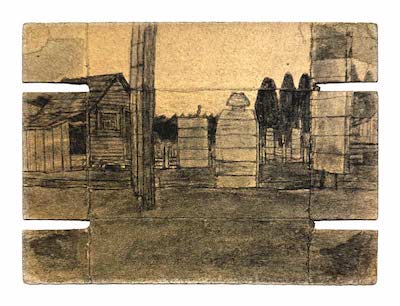

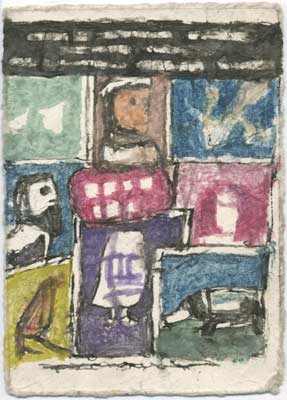

UNTITLED (interior window / farm landscape with obelisk), date unknown

Soot and saliva on found board, double-sided

5 x 7 inches

$20,000

|

The reverse side

click to enlarge any image |

_sm.jpg) |

_sm.jpg) |

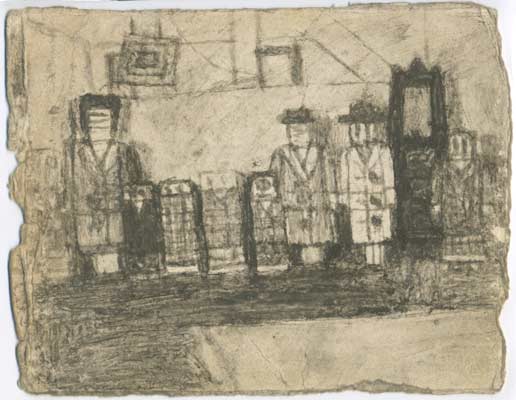

UNTITLED (friend in black jacket), date unknown

Soot on found paper, folded

4.5 x 2 inches

$45,000

|

The reverse side

click to enlarge any image |

_web.jpg) |

_web.jpg) |

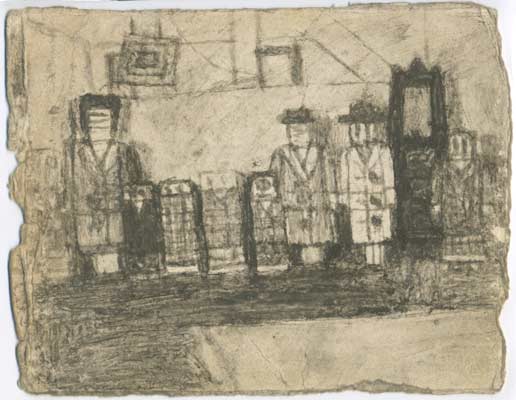

UNTITLED (Eugene Street houses / friend collection), date unknown

Soot and saliva on found board, double-sided

5.5 x 7.5 inches

$25,000

|

The reverse side

click to enlarge any image |

|

_sm.jpg) |

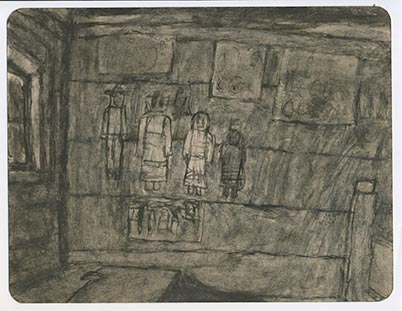

UNTITLED (interior / interior with friends), date unknown

Soot and saliva on found board

7 x 9.25 inches

$30,000

|

The reverse side

click to enlarge any image |

|

_sm.jpg) |

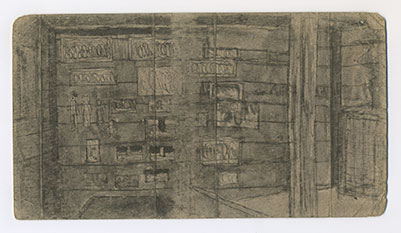

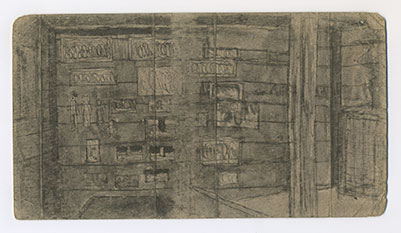

UNTITLED (double-sided interior display), date unknown

Soot and saliva on found board

4 x 7 inches

$20,000

|

The reverse side

click to enlarge any image |

|

_sm.jpg) |

UNTITLED (8 friends / abstract landscape), date unknown

Soot and saliva on found board

3.25 x 4.25 inches

$8,000

|

The reverse side

click to enlarge any image |

|

|

UNTITLED (shed under construction / boy and girl), date unknown

Soot and saliva on found board, double-sided

4.5 x 5.75 inches

$10,000

|

The reverse side

click to enlarge any image |

|

|

UNTITLED (family of friends / star house exterior), date unknown

Soot and saliva on found board, double-sided

5.5 x 7 inches

$25,500

|

The reverse side

click to enlarge any image |

|

|

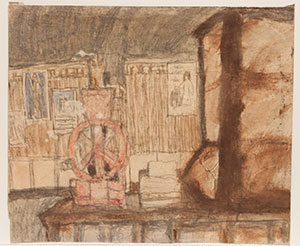

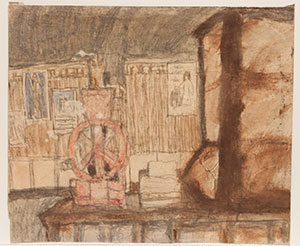

UNTITLED (interior with stove / interior with coffee grinder), 20th c.

Soot and color of unknown origin on paper.

8.5 x 10.25 inches

$10,000

|

The reverse side

click to enlarge any image |

|

|

|

_sm.jpg) |

UNTITLED (interior/Highway matches), date unknown

Soot and saliva on found board

5 x 9 inches

$15,000

|

The reverse side

click to enlarge any image |

|

_sm.jpg) |

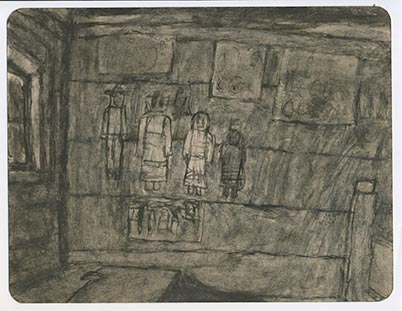

UNTITLED (4 friends on wall / Progress Tailoring company), date unknown

Soot and saliva on found board

8 x 10.5 inches

$20,000

|

The reverse side

click to enlarge any image |

|

|

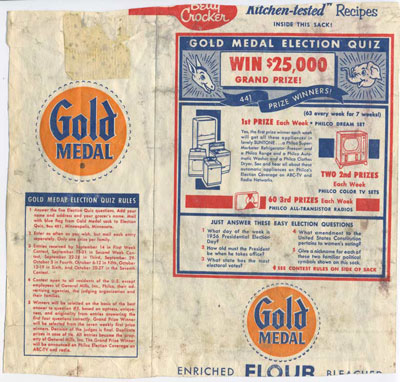

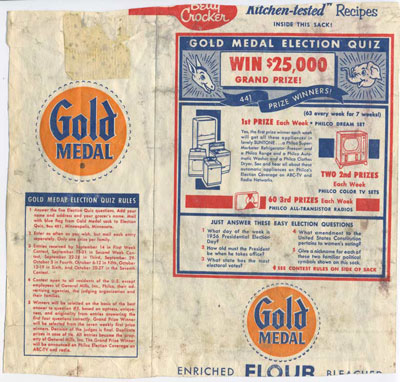

UNTITLED (soldier and family / Gold Medal flour), date unknown

Color of unknown origin on found paper

8 x 8.5 inches

$14,300

|

The reverse side

click to enlarge any image |

_web.jpg) |

_web.jpg) |

UNTITLED (KEEP), date unknown

Soot and saliva on found board

5 x 8 inches

$14,300 |

The reverse side

click to enlarge any image |

_web.jpg) |

_web.jpg) |

UNTITLED (attic with friends), date unknown

Soot and saliva on found board

7 x 9.5 inches

$18,300 |

The reverse side

click to enlarge any image |

_web.jpg) |

_web.jpg) |

UNTITLED (attic with friends / graham crackers), date unknown

Soot and saliva on found board

6 x 8 inches

$15,300 |

The reverse side

click to enlarge any image |

_web.jpg) |

_web.jpg) |

UNTITLED (cobbler / Progress Tailoring Co.), date unknown

Color of unknown origin on found paper

9.5 x 8 inches

$15,300 |

The reverse side

click to enlarge any image |

_web.jpg) |

_web.jpg) |

UNTITLED (boxers / gold medal flour), date unknown

Soot and saliva on found board

10 x 8 inches

$20,000 |

The reverse side

click to enlarge any image |

Read more about James Castle. See description of James Castle here.

click to enlarge any image:

UNTITLED (room with beds), date unknown

Soot and saliva on found board

9.5 x 9.5 inches

$10,000

UNTITLED (tower building), date unknown

Soot and saliva on found board

7 x 8 inches

$8,000

UNTITLED (3 female figures with patterned dress and green color), date unknown

Soot and saliva on found board

10 x 11 inches

$12,000

UNTITLED (monument), date unknown

Soot and saliva on found board

7 x 8 inches

$8,000

UNTITLED (truck with Asian lettering in bright colors), date unknown

Soot and saliva on found board

9 x 12 inches

$12,000

UNTITLED (teacher with classroom in pastel colors), date unknown

Soot and saliva on found board

13 x 10 inches

$14,000

UNTITLED (10 friends), date unknown

Soot, saliva, and color of unknown origin on found paper

3.5 x 6 inches

SOLD

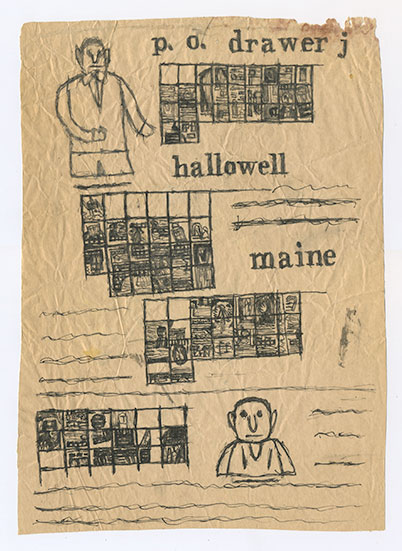

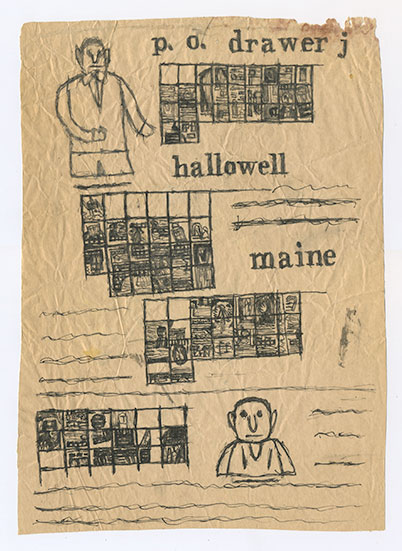

UNTITLED (P.O. drawer j), date unknown

Soot and saliva on found paper

12.5 x 9 inches

$18,000

UNTITLED (red stamp / Certi-fresh chocolate ice cream), date unknown

Color of unknown origin on found board

6.75 x 5 inches

$8,450

UNTITLED (small pictures / Home Dairies vanilla ice cream), date known

Color of unknown origin on found board

7 x 4.75 inches

$8,000

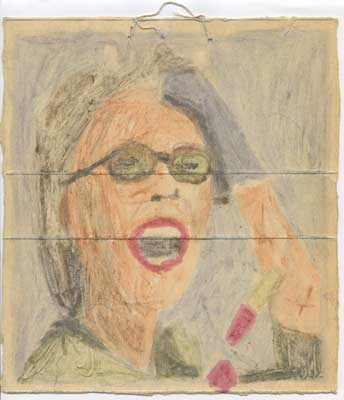

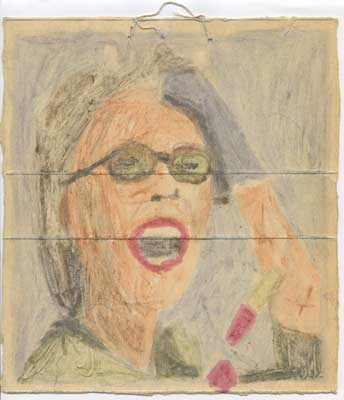

UNTITLED (lipstick ad / Kraft macaroni and cheese), date unknown

Color of unknown origin on found board

8.5 x 7.5 inches

$14,300

_sm.jpg)

UNTITLED (clean), date unknown

Found paper and wheat paste

3.5 x 2 inches

$1,400

web.jpg)

UNTITLED (gadgets), date unknown

Found paper and wheat paste

1.5 x 4 inches

$1,400

_web.jpg)

UNTITLED (loose), date unknown

Found paper and wheat paste

1.75 x 4.5 inches

$1,400

_web.jpg)

UNTITLED (pledges), date unknown

Found paper and wheat paste

1.75 x 4.5 inches

$1,400

Installation views of James Castle Drawing, 2019

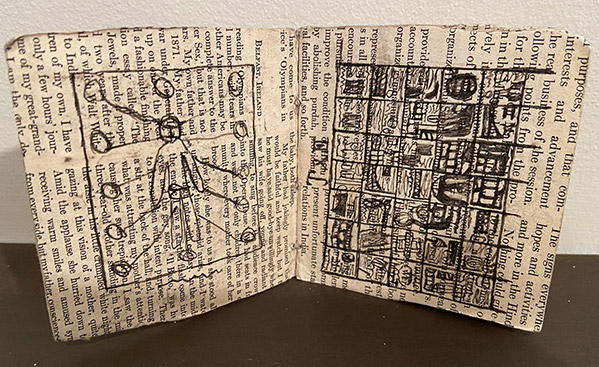

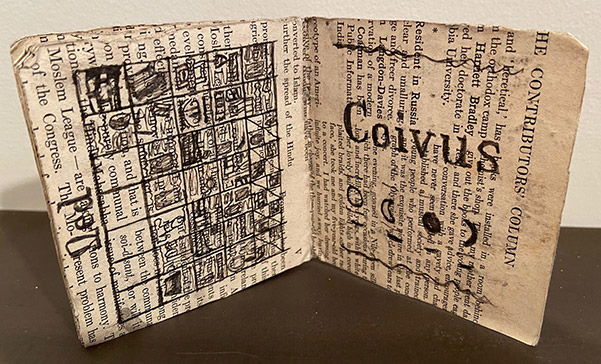

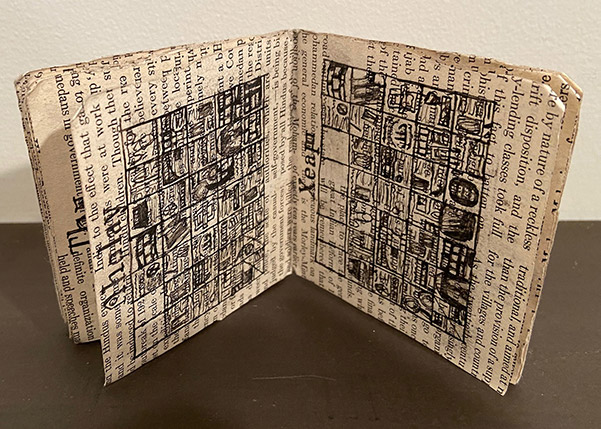

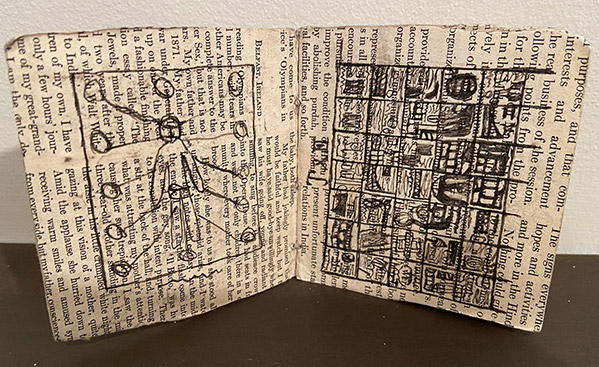

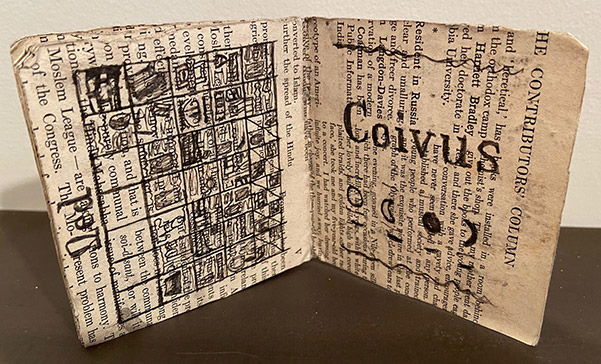

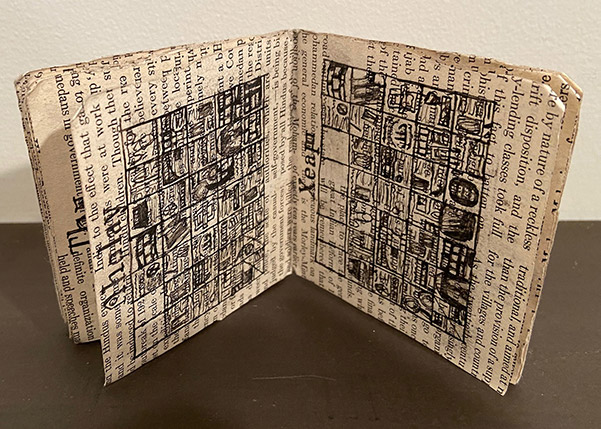

UNTITLED (St. Luke's Hospital Book-14 pages), date known

Soot and saliva on paper

3.5 x 6.25 inches

$15,000

The following article is taken from the Village Voice, April 26 - May 2, 2000 issue:

Home Alone - Visual art review from the exhibition at The Drawing Room, New York by Jerry Saltz

Drawing is one of the roots of art. It's a way of seeing and thinking, a way of seeing yourself think. An intimate art about cosmic things, and a cosmic art about intimate things, it happens mostly—but not always—sensually, physically, from the fingertips. The nerve endings of the hand listen to the musings of the imagination, which marvels at the movements of the hand. The artist's face is often very near the drawing. In ways it's very primitive, very primary, a kind of universal language. Drawing makes old thought new and new thought accessible. Without it—in whatever form it takes—there might be no art. To James Castle, the deaf, mute, reputedly mentally handicapped and illiterate artist, who died in 1977 at the age of 77, drawing was all there was.

It makes sense that Jay Tobler curated "House Drawings," the first exhibition of this relatively unknown "folk artist" (a term that sounds more pejorative and irrelevant every day). Tobler, who died of leukemia at 33, seven days before the opening, was as versed in "self-taught" art as he was in New York's high-powered art world (as the former director of Barbara Gladstone Gallery). An early proponent of UFO artist Ional Talpazon, Tobler included "outsiders" like Bill Traylor and Howard Finster alongside Whistler and Ryder in the reference book he edited for Phaidon Press, The American Art Book.

I'm guessing that Tobler was attracted to Castle because he (like Talpazon) exhibits tendencies not usually associated with outsider artists. Castle did more than simply repeat the same gesture, theme, or tic—a definition many apply to folk artists, who supposedly work without developing. Castle, who never learned to sign or speak, and who never ventured more than 150 miles from his birthplace in southwestern Idaho, made thousands of meticulously illustrated books and as many drawings. Some contain made-up hieroglyphic symbols organized into grids, others are pages of stamp-sized portraits drawn in herringbone patterns and organized like imaginary family photo albums. (A selection of Castle's books are currently on view at the American Institute of Graphic Arts, 164 Fifth Avenue, through May 12.) He worked on butcher paper, matchbook covers, cardboard, and mail-order catalogs (his parents' home served as the local post office), and made pens from sharpened sticks, ink from soot and spit, and sometimes fashioned paper from chewed-up pulp.

At the Drawing Room, you can see Castle draw a building from one side, then another; then he renders it from closer in, then crops the same scene differently. Other times, he might add a little color, sew string into the paper, cut an object out of cardboard, or draw from two perspective points simultaneously, as in an almost mystical rendition of a staircase. A town landscape is pictured in muted color, then he moves a little farther back and does it in black and white. Another work, reminiscent of the early American modernist Oscar Bluemner, features a herringbone-patterned house, a tree of stripes, and a cloud of Xs. Castle's drawings can get muddy, but he always seems to be wondering, "What would this look like from here?" This is what brings him very close to our art world. Now, thanks to Tobler and Catherine de Zegher, director of the Drawing Center (who organized the recent stunning Sergei Eisenstein show), we can get closer to Castle's world.

Initially, I was sorry the show was devoted only to those drawings having to do with home, but concentrating on one theme allows us to see Castle the artist, rather than the idiot savant or the outsider. His domestic interiors and tranquil outdoor scenes bring him closer to someone like Édouard Vuillard than to Howard Finster. Several drawings of a small town and one of the paneled side of a building bring to mind the deadpan Depression realism of Walker Evans, as well as George Ault's visionary precisionism.

Castle was especially good at establishing complex stratas of space. In one drawing of a farmhouse, he positions himself just beyond the building, so that the porch is very close-up, then there's the yard, some trees, a stable, then another house, hills, then sky. By the time your eye reaches the back of the drawing, you've traveled an enormous metaphysical distance.

In the indoor drawings, he might focus on a door seen from the side, just a molding, two plates on a cupboard, or the ceiling as seen from the floor. His pictures of beds and bedrooms can stand beside van Gogh's without losing much. One features an open door through which we catch a tantalizing glimpse of an old-fashioned wood-burning stove in the kitchen and a shaft of sunlight through a window. Everything is quiet, private, and almost unknowable. Back inside the bedroom, the eye relishes a messy dresser top and Castle's own pictures hung crookedly on wallpapered walls. In another work, he moves about three feet to the left and redraws the scene, this time conjuring a more contained space. Finally, he goes around the side of the bed and draws it again.

Castle's eye was like a camera's; he saw everything equally, and equally well. He used drawing to caress and examine everything in his sight. Castle's world is always cast in twilight—you could call it dark, and even dour—but his drawings also speak of a tremendous love of one's surroundings, and a passion for rendering them again and again. Drawing set Castle's senses free; looking at his art makes ours come alive as well.

In 1999, Guy Trebay of The Village Voice described Castle's work saying, "The spit-and-soot drawings Castle made with a pointed stick could probably hold their own in any art context. His hand-sewn constructions of cardboard and twine strike resonances with the work of artists from Thomas Schütte to Joseph Beuys. That Castle was deaf from birth, and never learned to speak, sign, read, write, or finger spell; that he refused all schooling and lived with his parents in a mountain town near Boise, Idaho, are 'the most important facts of his life and artmaking,' as one critic claims. These are certainly the first things you hear anyone talk about when they look at the work."

© The Village Voice, 2000

|

_sm.jpg)

_sm.jpg)

_web.jpg)

_web.jpg)

_sm.jpg)

_sm.jpg)

_sm.jpg)

_sm.jpg)

_sm.jpg)

_web.jpg)

_web.jpg)

_web.jpg)

_web.jpg)

_web.jpg)

_web.jpg)

_web.jpg)

_web.jpg)

_web.jpg)

_web.jpg)

_sm.jpg)

web.jpg)

_web.jpg)

_web.jpg)