Prints

Editioned works: price and availability subject to change as edition sells out

About

“I have never tried to make illustrations of apartheid, but the drawings and films are certainly spawned by and feed off the brutalized society left in its wake. I am interested in a political art, that is to say an art of ambiguity, contradiction, uncompleted gestures, and certain endings; an art (and a politics) in which optimism is kept in check and nihilism at bay. ”

Exhibitions

-

William Kentridge (born 28 April 1955) is a South African artist best known for his prints, drawings, and animated films, especially noted for a sequence of hand-drawn animated films he produced during the 1990s. The latter are constructed by filming a drawing, making erasures and changes, and filming it again. He continues this process meticulously, giving each change to the drawing a quarter of a second to two seconds' screen time. A single drawing will be altered and filmed this way until the end of a scene. These palimpsest-like drawings are later displayed along with the films as finished pieces of art.

Kentridge has created art work as part of design of theatrical productions, both plays and operas. He has served as art director and overall director of numerous productions, collaborating with other artists, puppeteers and others in creating productions that combine drawings and multi-media combinations.

William Kentridge has gained international recognition for his distinctive animated short films and for the charcoal drawings he makes in producing them. Kentridge works in theater and has so for many years, initially as set designer and actor, and more recently, director. Since 1992 he has collaborated with Handspring Puppet Company creating multi-media pieces using puppets, live actors and animation. Throughout his career he has moved between film, drawing and stage yet his primary focus remains drawing, seeing his theatre and film work as an expanded form of his drawing.

Since Kentridge participated in Dokumenta X in Kassel (1997), solo shows of his work have been exhibited at the Museum of Modern Art (New York) and Museum of Contemporary Art (San Diego). A large survey exhibition in 1998-1999 toured Barcelona, Brussels, Graz, London, Munich and Marseille.

In 1999 he was awarded the Carnegie Medal. In 2001 and 2002, a survey of Kentridge's work traveled to museums in the United States and was seen in Chicago, Houston, Los Angeles, New York and Washington DC. In May 2002 Kentridge was awarded an Honorary Doctorate in Fine Art from the Maryland Institute of Contemporary Art in Baltimore.

Kentridge sees his work as rooted in Johannesburg, South Africa, where he continues to live today with his wife and three children.

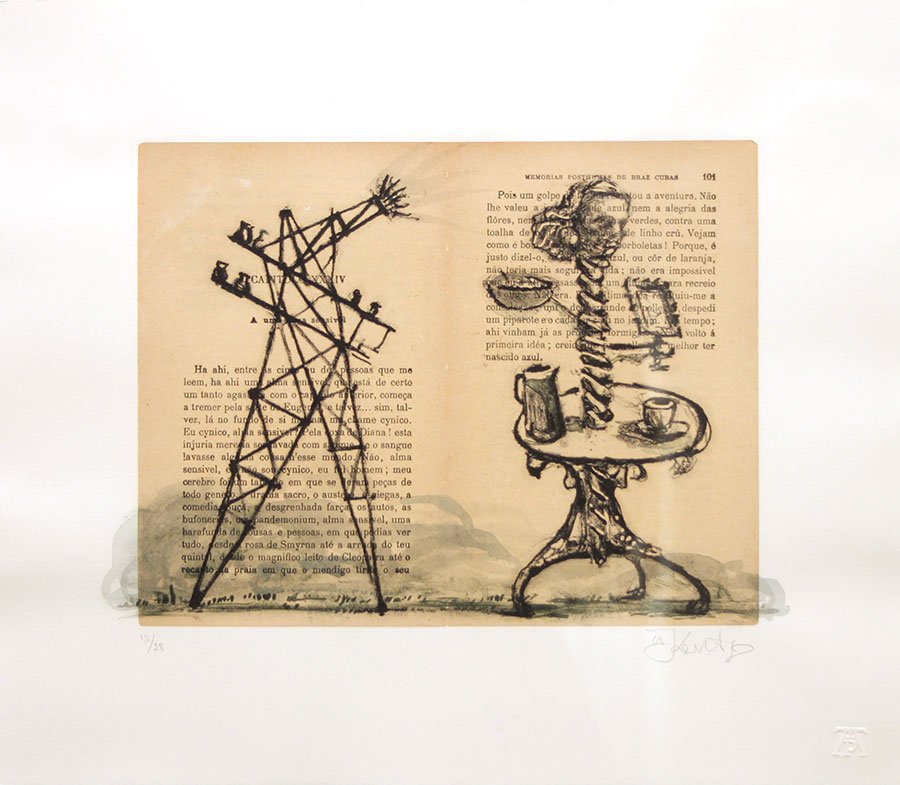

A special thanks to David Krut, publisher, for his support in our exhibitions of Kentridge's works.Prints with Collage or Hand-coloring

In April 2000, Kentridge headed to 107 Workshop in Wiltshire, England, to work on new large format etchings exploring the imagery of his current work. These editions reflect a procession of figures that the artist had created for casting in bronze. They move in a circular procession within the large etched circle - an inward direction in the first and outwards in the second.

The film Procession was shown at the Prince Klaus Fund Awards in December 1999 in the Palace of the Queen of the Netherlands, Amsterdam on a screen which was the ceiling of the room, one hundred feet high.

The artist worked on the large copper plates for each of the images, using the traditional intaglio processes of etching, aquatint and drypoint. A letterpress plate then added maps from an atlas into the large circles. These are sections of maps found by the artist in an old atlas - the Islands between Greece and Turkey in the first, and the Islands of the China Sea in the second print. The map areas were scanned and enlarged using computer technology to allow the production of heavy duty nylon polymer plates that were produced in Johannesburg and shipped to the Workshop.

The artist has added extensive brush strokes of different grey watercolors to the areas around the circle and into the margins and the prints are fully worked to the edges of the paper.

- David Krut, publisher -

Born in Johannesburg, South Africa in 1955; works and lives in Johannesburg

SELECTED ONE-PERSON EXHIBITIONS

2003

Drawings and Editions, Greg Kucera Gallery, Seattle

William Kentridge: New York Editions, Barbara Krakow Gallery, Boston

William Kentridge: New York Editions, Marian Goodman Gallery, New York

2001

The New Museum of Contemporary Art, New York

William Kentridge: A View of Personal Conflicts Set Against the Background of South Africa, Hirshhorn Museum, Washington, DC

William Kentridge: Ubu Tells the Truth and Other Stories - Works from Valley Collections, Nelson Fine Art Center, Arizona State University Art Museum, Tempe

Prints and Drawings, Greg Kucera Gallery, Seattle

Gracie Mansion, New York

2000

46th International Short Film Festival, Internationale Kurzfilmtage Oberhausen, Germany (South African representative)

1999

Museo d'Arte Contemporani de Barcelona, Barcelona (survey exhibition)

Projects 68, Museum of Modern Art (Project Room), New York

MIT List, Cambridge, MA

Serpentine Gallery, London (survey exhibition)

Centre de la Vielle Charite, Marseille (survey exhibition)

Neue Galerie Graz, Austria (survey exhibition)

Premiere of Stereoscope, Marian Goodman Gallery, New York

Paris Goodman Gallery, Johannesburg

1998

The Drawing Centre, New York Museum of Contemporary Art, San Diego Museum of Contemporary Art, San Diego

Stephen Friedman Gallery, London

Societe des Expositions du Palais des Beaux-Arts de Bruxelles, Brussels

Kunstverein Munchen, Munich (survey exhibition)

1997

Applied Drawings, Goodman Gallery, Johannesburg

1996

Eidophusikon, Annandale Galleries, Sydney

1994

Felix in Exile, Goodman Gallery, Johannesburg

1993

Ruth Bloom Gallery, Los Angeles

1992

Drawings for Projection, Goodman Gallery, Johannesburg (traveling to Vanessa Devereux Gallery, London)

1991

Five Gouache Collage Heads, Newtown Galleries, Johannesburg

1990

William Kentridge: Drawings and Graphics, Cassirer Fine Art and Gallery on the Market, Johannesburg

1989

Responsible Hedonism, Vanessa Devereux Gallery, London

1988

Cassirer Fine Art, Johannesburg

1987

In the Heart of the Beast, Vanessa Devereux Gallery, London

Standard Bank Young Artist Award (an associated exhibition in Grahamstown toured nationally)

1985

AA Vita Award for William Kentridge, Cassirer Fine Art, Johannesburg

Cassirer Fine Art, Johannesburg South African Arts Association, Pretoria

1984

Market Theatre Award for New Visions

1981

Domestic Scenes, The Market Gallery, Johannesburg

1979

The Market Gallery, JohannesburgSELECTED GROUP EXHIBITIONS

2004

The Divine Comedy: Francisco Goya, Buster Keaton, William Kentridge, Vancouver Art Gallery, BC, Canada

2002

One Thousand Words: Storytelling Images from Cultures Around the World, John Michael Kohler Arts Center, Sheboygan, WI

2001

Change no Sorry, Joao Ferreira Fine Art, Cape Town, South Africa

Text: Read All About It!, Greg Kucera Gallery, Seattle

2000

Carnegie International 1999/2000, Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh, PA

3rd Shanghai Biennale, Shanghai Art Museum, China

Emergence, Standard Bank Gallery, Johannesburg

Lasting Impressions: Contemporary Prints from the Bruce Brown Collection, Portland Museum of Art, ME

1999

La Memoire (1999 phase of La Ville, Le Jardin, La Memoire), Academie de France a Rome, Villa Medici, Rome

Act 1 (1999 phase of Act 1, Act 2, Act 3), Kunstforening, Copenhagen

48th International Venice Biennale: d'APERT utto, Giardini di Castello and the Arsenale, Venice

The Passion and the Wave, 6th Istanbul Biennale, Istanbul (South African representative)

Unfinished History, Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago

A Sangre y Fuego / No Quarter Given, Espai d'art Contemporanea di Castello, Spain

Life Cycles, Galerie fur Zeitgenssische Kunst, Leipzig

Tachikawa Arts Festival, Tachikawa

1998

Vertical Time, Barbara Gladstone Gallery, New York

Nominee for Hugo Boss Prize, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York

Shoot at the Chaos, SPIRAL/Wacoal Art Center, Tokyo

Breaking Ground, Marian Goodman Gallery, New York

XXIV Bienal de Sao Paulo, Sao Paulo (South African representative)

Unfinished History, Walker Art Center

Museo de la Ciudad, Mexico City

1997

Sexta Bienal de la Habana El Individuo y su Memoria, Cuba

Citte/Nattura: Mostra Internazionale di Arte Contemporanea, Villa Mazzante, Rome

Documenta X, Museum Fredericianum, Kassel

Truce: Echoes of Art in an Age of Endless Conclusions, Site Santa Fe, NM

2nd Johannesburg Biennale Trade Routes: History and Geography, Johannesburg

Les Arts de la Resistance: Fin de Siecle, Johannesburg, Galerie Michel Luneau, Nantes

Delta, ARC Musee d'Art Moderne de la Ville Paris, Paris

UBU 101, collaborative exhibition with Deborah Bell and Robert Hodgins, Standard Bank National Festival of the Arts, Grahamstown

1996

Simunye: We Are One, Adelson Galleries, New York

Faultlines, The Castle, Cape Town

10th Sydney Biennale Jurassic Technologies Revenant, Sydney

Ici et Ailleurs, film section within Inklusion-Exklusion, Graz

Don't Mess with Mr. In-between, Culturgest, Lisbon

Campo 6: The Spiral Village, Galleria Civica d'Arte Moderna e Contemporanea, Turin

Colours: Art from South Africa, Haus der Kulturen der Welt, Berlin

1995

Africus 1st Johannesburg Biennale: Memory and Geography, collaboration with Doris Bloom

Memory and Geography, collaboration with Doris Bloom, Stefania Miscetti Gallery, Rome

Panoramas of Passage: Changing Landscapes of South Africa, touring USA and South Africa

Mayibuye iAfrika, Bernard Jacobson Gallery, London

On the Road, Delfina Studio Trust, London

4th Istanbul Biennale Kentridge exhibition Eidophusikon

1994

Trackings: History as Memory, Document and Object, Art First, London

Displacements, Block Gallery, North Western University, Chicago

Spacex Gallery, University of Exeter, UK

1993

Easing the Passing of the Hours, Goodman Gallery, Johannesburg

45th Venice Biennale South African group exhibition, In Croc Del Sud

1991

Little Morals, collaboration with Deborah Bell and Robert Hodgins, Taking Liberties Gallery, Durban

1990

Art from South Africa, Museum of Modern Art, Oxford, touring UK

1988

African Encounters, Dome Gallery, New York, touring to Washington DC

1986

Claes Eklundh, William Kentridge, Thomas Lawson, Simon/Neuman Galleries, New York

But this is the Reality, The Market Gallery, Johannesburg

1985

Cape Town Triennial '85, South African National Gallery, Cape Town

Tributaries, Market Theatre precinct; touring Germany

1984

Hogarth in Johannesburg, collaboration with Deborah Bell and Robert Hodgins, Cassirer Fine Art, Johannesburg (toured nationally)SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY

Jennifer Stone, 'Freud's Body Ego or Memorabilia of Grief: Lucian Freud and William Kentridge', www.javaribook.com

Michael Godby, 'Robert Hodgins, William Kentridge and Deborah Bell: Hogarth in Johannesburg', Witwatersrand, University Press, Johannesburg, 1990

Michael Godby, 'William Kentridge: Four Animated Films', in William Kentridge: Drawings for Projection, Goodman Gallery, Johannesburg, 1992 (catalogue)

'4th International Biennale of Istanbul,' The Istanbul Foundation for Culture and Arts, 1995 (catalogue)

Sue Williamson, 'Ashraf Jamal, Art in South Africa: The Future Present', David Philip, Cape Town/Johannesburg, 1996

'Delta', ARC Musee d'Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris, Paris, 1997 (catalogue)

Catherine David and Jean-Francois Chevrier, 'Politics -Poetics Documenta X the book', Museum Fredericianum, Kassel, Cantz Verlag, Ostfildern-Ruit, 1997 (catalogue)

Rory Doepel, 'Ubu 101: William Kentridge, Robert Hodgins, Deborah Bell', Observatory Museum, Standard Bank National Festival of the Arts, Grahamstown, 1997 (catalogue)

Jurassic Technologies Revenant, 10th Sydney Biennale 1997, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Artspace, Ivan Dougherty Gallery, 1997 (catalogue)

Sexta Bienal de Habana: el individuo y su memoria, Centro Wilfredo Lam, Havana, 1997 (catalogue)

'Truce: Echoes of Art in an Age of Endless Conclusions', Site Santa Fe, New Mexico, 1997 (catalogue)

Michael Godby, 'William Kentridge's History of the Main Complaint: Narrative, Memory, Truth', in Sarah Nuttal and Carli Coetzee, Negotiating the Past: the Making of Memory in South Africa, Oxford University Press, Cape Town, 1998

Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev, 'William Kentridge, Palais des Beaux-Arts de Bruxelles', Brussels, 1998 (catalogue) -

"Freud's Body Ego or Memorabilia of Grief: Lucien Freud and William Kentridge”

e-book by Jennifer Stone (courtesy javaribook.com, copyright 2003)William Kentridge will direct the New York premiere of a multi-media theatre event, "Il ritorno di Ulisse" ("The Return of Ulysses"), in March 2004, in New Visions, part of the Great Performers series of 2003-2004 at Lincoln Center. The opera is a version of Monteverdi's "Il ritorno di Ulisse in patria," first performed in Venice in 1640, with a libretto by Badoaro. Kentridge's opera, "Zeno at 4am" (based on Svevo's novel, "Zeno's Conscience" of 1923), was staged in the same festival in the 2001-2002 season, followed by performances in Brussels, Belgium and at Dokumenta XI in Kassel, Germany. Next year's Monteverdi production, set round a hospital bed, features the Handspring Puppet Company, life-size puppets along with puppeteers who, in an uncanny way, seem to take on the carved wooden dolls' stiff features and graceful gestures. A Kentridge dramatization assumes a European musical score in order to transmute it into an African context, accompanied by a rear-projected parade of his filmed drawings and shadow figures or silhouettes in a meta-narrative of unpredictable and unforgettable imagery. Kentridge trained, in the early 1980s in Paris at Ecole Jacques Lecoq where he says he learned more about the history of art through dramaturgy than the Academy. Criticism that dwells on the contours of Kentridge's landscapes and on questions of technique ignores the profundities of his mind at work rethinking art, film, theatre and opera. Conspicuous details betray subtleties of a literary spirit versed in European culture alongside African heritage. Kentridge quite simply causes astonishment. Kentridge is this year's recipient of the prestigious Goslar Kaiserring Award, the ceremony to take place in early October 2003. He has been invited to install an exhibition in the Munchehaus Museum in the German medieval town. (Previous artists to receive the award include Henry Moore, Max Ernst, Alexander Calder, Joseph Beuys, Richard Serra, Willem de Kooning, George Baselitz, Gerhard Richter, Anselm Kiefer, Ilya Kabakov, Sigmar Polke, Cindy Sherman, and Christian Boltanski.)

"William Kentridge"

by Janet Koplos

Art in America

December, 2002"One of the fascinating things about William Kentridge's films is how they let the process show. Because he draws, shoots, erases and shoots again to create his imagery - rather than painting animation cells or digitally developing scenes - I am conscious of his means, even his touch. It was Kentridge's genius to show how the directness of drawing could survive the indirectness of a camera-based art."

“William Kentridge: 12 African Greats Speak Freely About Their Continent”

Interview Magazine

May 22, 2001"I live in Johannesburg. All the places I've lived are within a four or five-kilometer radius of each other. Like most South African Jews, my grandparents and great grandparents came from Lithuania at the turn of the century. I grew up in a liberal family with politically involved parents who were lawyers. I can't remember a stage where I was not aware of living in an unnatural place. There was so much dinner table conversation about the inequities of the society we were living in--that was a kind of daily bread and butter. This is not unique, but it was less than common in white society. There was always a sense growing up of living in a society that was waiting to become an adult, to change. During the 1970s and '80s that seemed completely intractable, and it's that sense of waiting--which existed throughout my childhood--that had been a false expectation. Then when the transformation came in 1989 through 1994, this was a kind of vindication of all those expectations of childhood. I think one of the exciting things about South Africa after this transformation from apartheid is that it has an open-ended future. Being objective, I don't know how one's going to solve the enormous problems facing South Africa. The largest problem is how to deal with the AIDS epidemic. Both in terms of medicine--how do we stop so many people dying and how do we look after people who are ill--but, also, how do we deal with a bruised society left in the wake of the epidemic? If life becomes so dispensable, if people die with such little cause, so easily, what is the status one puts on the value of life, on long-term projects, on a sense of the future, on a sense of beneficent fate? All those things get thrown out of kilter. One misconception about Africa would be that it's a uniform, unified category, that you can talk about Africa in a meaningful way. That implies that Africans, whether they are in Egypt or Tunisia or Togo or South Africa, are people that can be talked about as if they were not identical, but certainly similar enough. So that would be the first misconception. The second misconception would be that societies in Africa are essentially pre-modern. It's about understanding the ongoing clash between different kinds of modernization. If you look at 99 percent of the conflict throughout Africa, it has to do with conflicts over modernization; who owns resources and who has access to them, who is able to transform their lives from rural peasantry to an urban society.” - William Kentridge

“William Kentridge: Ghosts and Erasures”

by Leah Ollman

Art in America

January 1999Since 1989, Johannesburg native William Kentridge has been making short, animated films from charcoal drawings that he alters and erases in the course of filming. Like dense, insistent poems, the films move through time on the momentum of associations, loves, fears and memories exhumed both willfully and reflexively. Like Kentridge's animation process itself--born of the desire to keep alive the transient, evolutionary stages of his drawings -- the unscripted narratives of the films reckon with the tenuous nature of memory, both personal and historical. How much are we to hold onto the past as a way of navigating the future, and how much to let it go or suppress it as an impediment to progress? Kentridge's drawings for projection chronicle, on a visceral level, his country's transitions. After decades under a cruelly rigid template, South Africa is now drawing itself, drafting, erasing and reformulating its structures of power, its social relations, its systems of rights, benefits and protections. The fluidity and contingency of drawing lie at the heart of all of Kentridge's art of the past 20 years, not just his work on paper. In the films, however, an unusual, reciprocal dynamic comes into play between the drawings that comprise the visual fabric of the films and the films themselves. Unlike conventional cell animation, which fuses thousands of drawings into a slick, seamlessly continuous whole, Kentridge's process is overtly raw and hand-wrought. For each film (all are under 10 minutes) Kentridge makes about 20 drawings, which undergo continual addition, permutation and erasure, the traces of which are plainly visible, yielding an impression of time and space as viscous, invariably altered by every arrival and departure. 'You could look at the drawings as indicative of the process and the route to making the film,' he says. 'You can also see the finished film as the complicated way of arriving at that particular suite of drawings.

“William Kentridge Answers a Few Questions”

One People Voice, 1998OnePeople met with William Kentridge on the eve of our journey's end. After hearing so much about his work from his South African peers, and seeing examples of his work at the Biennale, we were eager to spend time with him, recording his thoughts. Following our return to the United States, Kentridge was one of three finalists for the 1998 Hugo Boss award. A rather stoic individual, Kentridge greeted us warmly at his studio where we had a chance to see some works-in-progress. Tracing the evolution of his work, one can easily appreciate the growing magnitude of his creative projects. Beginning with two-dimensional charcoal drawing on paper, Kentridge soon included the element of time to his drawings through the medium of film. Returning to the drawing board after a few years, he then incorporated the element of space to his work with the addition of the Handspring Puppet Company. Ubu and the Truth Commission, an internationally heralded piece of theater, has in turn led Kentridge to the addition of audio dynamics - in the name of opera.

Question 1: Your works appear very labor intensive. How long did it take you to create "Stereoscope?" Can you talk a little bit about the significance of your laborious process and how you maintain momentum and focus? The work is very labor intensive. "Stereoscope" took 9 months to make - with some breaks for travel and exhibitions during that period. It takes a long time because there is no script or storyboard - the ideas are worked out in the making. In the construction of Stereoscope, most of the first four months work had to be abandoned. WK: Momentum - because the work is so slow, unless one works fast and intensely, the project would never get finished. So one has to begin each day running. Making the film is about finding the focus, finding what the film is about. If the film had been storyboarded, it would be difficult to maintain focus; but because it is thought out as it is done, that becomes part of the subject.

Question 2: The music in "Stereoscope" is very striking. Was it composed specifically for the work? If so, were you involved in that process? WK: Music. Philip Miller, a South African composer, wrote the music for the film. He has written music for four of my films. His involvement comes at quite an early stage - after a couple of months, when there are a few minutes of rushes to look at, we sit look at them at an editing table, with different pieces of music - anything from Monteverdi to jazz - and try to understand the musical grammar of the film. From then on we work closely, and the music becomes more and more precise as the film nears completion.

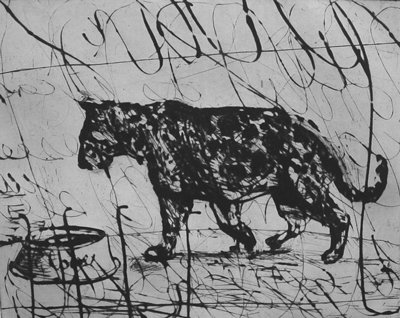

Question 3: Are the recurring elements (like the cat and the blue line, etc.) in your work symbolic of something? They seemed meaningful, but I wasn't sure of what. WK: Re the cat and blue line. I never start with a meaning, so cannot tell you what the cat symbolizes, if anything - I simply knew that I needed a cat at that moment of the film. Blue lines are simply a literal drawing of different lines of communication in the film.

Question 4: Why did you choose to use a split screen in some parts of the video? WK: Come on! The film is called "Stereoscope," a machine that needs two separate images to make one three-dimensional view. Any more clues needed?

Question 5: Was "Stereoscope" inspired by specific events in South African history? WK: No specific events in South African history. The section of chaos in the city towards the end of the film contains images from newspapers and TV from the weeks in which I was working on that part - police beating students in Jakarta, Indonesia; riots outside banks in Moscow, Russia; rebels being thrown over a bridge, and then shot at in the river below, Kinshasa, Congo; someone picking up rubble to throw at a building - US embassy in Nairobi, Kenya. But of course the images are all of Johannesburg.

Linocut on Tableau rice paper

97.5 x 40 inches

Edition of 25

Price on request