June 1 - July 15

First Thursday Reception, June 1, 6-8pm

Curatorial walk through: Saturday, June 3 at noon

Review in Crosscut, JUNE 2017

Hard truths about class and race from those who do the work

by Rosemary Ponnekanti

http://crosscut.com/2017/06/hard-truths-about-class-and-race-from-those-who-do-the-work/

Review in CityArts Magazine, JUNE, 27 2017

The Help: The Work's Not Over

by Margo Vansynghel

http://www.cityartsonline.com/articles/help-work's-not-over

¡Cuidado! - The Help

This exhibition focuses on America's strained, and often tenuous, relationship to its various domestic workers on

the home front, as well as the workforce doing the menial and entry level jobs on the business front.

Whether Nanny, Butler, Gardener, Maid, Handyman, or Housecleaner, the American Family cannot simply do

without the help of these workers. Busboys, Servers, Housekeeping Maids, Security Guards, Migrant Workers,

Home Health Caregivers, and Dishwashers are job titles that bear little status but without which many businesses,

both large and small, could not survive.

Artists included in this exhibition are: Juventino Aranda, Jack Daws, Ramiro Gomez, Patrick Kam, Paul Rucker,

Alison Saar, Betye Saar, Joyce Scott, Roger Shimomura, John Sonsini, Rodrigo Valenzuela, Kara Walker, and

Lynne Yamamoto.

My gallery has not and will not shy away from politically based art. This exhibition is, in many ways, a protest

against Donald Trump and his battle against those at the bottom of the economic ladder. Trump's divisive rhetoric

on the campaign trail; his threats made toward routing immigrants or halting immigration; and his promises to build

a wall at the Mexican border, all apparently sounded good to a great many Americans. But, given Hillary Clinton's

decisive win of the popular vote, a great many more Americans were not convinced of the good in those

opportunistic promises.

It was our hope to put this exhibition together during the 2016 campaign as the derisive vitriol increased and

Trump's candidacy took on its bitter tone. But we just couldn't get it together fast enough-and we hoped and

prayed that Clinton would prevail. Now, a few months into Trump's presidency, we've seen many of his policies

questioned and many of his campaign promises fail. Yet these urgent issues have not disappeared or even

lessened. Trump, and his policy makers, seem as determined as ever to diminish justice and to dismiss the

needs of the least powerful among us. The least fortunate ones in any society are often simply, "the other." Be

they immigrants who have gotten here legally or simply out of desperation; the uneducated or the disadvantaged;

or those who are made to assume the role of "the other" simply by being the minority rather than the majority.

Juventino Aranda

JUVENTINO ARANDA

UNTITLED (PALE HORSE Y HOMBRE), 2017

Cement, acrylic polyurethane, and live plants

28.5 x 26.5 x 45 inches

JUVENTINO ARANDA

UNTITLED (MAR-A-LAGO), 2017

Etched mirror, bronze frame, and corrugated cardboard cover frame

68 x 54 x 2 inches

Jack Daws

JACK DAWS

VIVA VILLA, 2007

Plastic tub, acrylic on aluminum, lacquer

18 x 16 x 22 inches

$3,000

JACK DAWS

VIVA ZAPATA, 2007

Plastic tub, acrylic on aluminum, lacquer

18 x 16 x 22 inches

$3,000

The ubiquitous dish tubs used in restaurants everywhere, are employed by Jack Daws to invoke the difference between the likely ordinary lives of Hispanic busboys as opposed to the illustrious history of Mexican hero-outlaws such as Pancho Villa and Emiliano Zapata.

Ramiro Gomez

RAMIRO GOMEZ

THE LAWN MAINTENANCE (After David Hockney's A LAWN SPRINKLER, 1967), 2014

Acrylic on canvas

48 x 48 inches

Collection of Greg Kucera and Larry Yocom

Ramiro Gomez has been working with images of the Latino domestic workers and home maintenance workers from affluent neighborhoods in Los Angeles. Before his career as an artist took off, Gomez was employed as a male nanny for the children of wealthy parents. In the small collage works, Gomez paints images of maids and nannies, gardeners and janitors, over ads from glamorous shelter and fashion magazines such as Town & Country and Architectural Digest and GQ. In the "Lawn Maintenance (after David Hockney's 'A Lawn Sprinkler,' 1967) painting, Gomez pays tribute to the low paid lawn care worker while also paying his respects to fellow artist David Hockney, and his early series of landscape paintings of an idealized southern California.

Patrick Kam

PATRICK KAM

DRAGON IRONS, 2008

Cast iron, wood, suitcase, table, service bell and motors

36 x 276 x 26 inches

$8,000

Detail of:

DRAGON IRONS, 2008

Both Patrick Kam's and Lynne Yamamoto's work reference the cultural commonality of the Asian laundry.

In Kam's work, the irons strain to crawl across the floor like Chinese dragons, their claws clattering against the floor. They vainly attempt to carry across the floor the suitcase to which they are harnessed, forever the immigrant, they carry that status, or lack thereof, forward.

Paul Rucker

PAUL RUCKER

WHEN WE WERE USEFUL, 2016

Projected Video/ or Large Monitor (screen image here)

Edition of 8

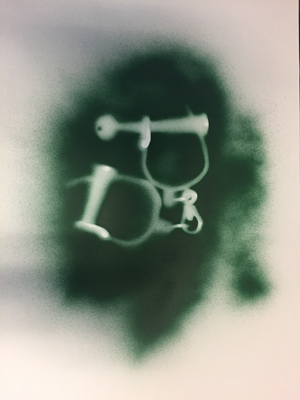

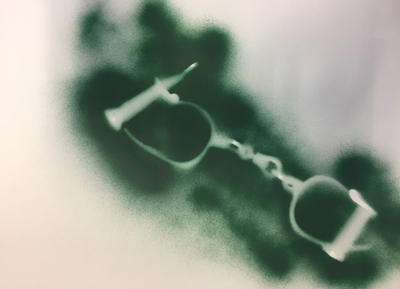

PAUL RUCKER

FORCED MIGRATION SERIES, 2016

Acrylic on Paper

13 x 19 inches

Edition of 21

Variable edition

PAUL RUCKER

FORCED MIGRATION SERIES, 2016

Acrylic on Paper

13 x 19 inches

Edition of 21

Variable edition

PAUL RUCKER

FORCED MIGRATION SERIES, 2016

Acrylic on Paper

13 x 19 inches

Edition of 21

Variable edition

Paul Rucker's work takes its point of departure from an illustration on a $100 Confederate bill showing slaves in a field of cotton Rucker has animated the engraved illustration to make the depicted slaves appear to be in endless, repetitive motion, forever tending the fields of their Master. Rucker's works from "Forced Migration" depict images of manacles which, like Kara Walker's silhouettes, are seen in a way that simultaneously clarifies the object and simplifies the horror of it.

Alison Saar

ALISON SAAR

Detail of: SKILLET PORTRAIT EMMA, 2002

Oil on skillet

13.5 x 10 x 2 inches

Collection of Driek and Michael Zirinsky

Alison Saar's portrait of a domestic worker, painted on the bottom of a frying pan, is barely visible. Invoking the relative invisibility of a typical household cook or kitchen maid, Saar paints the face with delicacy. Fittingly, the black on black image struggles to be seen amid the crusty surface of the frying pan's bottom, the side that takes the heat of the cooking flame.

ALISON SAAR

SKILLET PORTRAIT EMMA, 2002

Oil on skillet

13.5 x 10 x 2 inches

Collection of Driek and Michael Zirinsky

Betye Saar

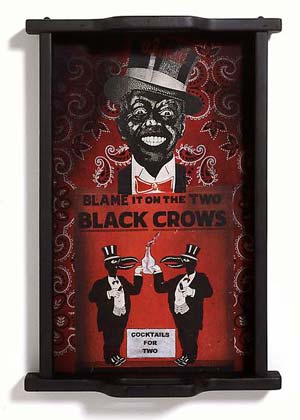

BETYE SAAR

COCKTAILS FOR TWO, 1999

Mixed media assemblage

21 x 14.5 x 3 inches

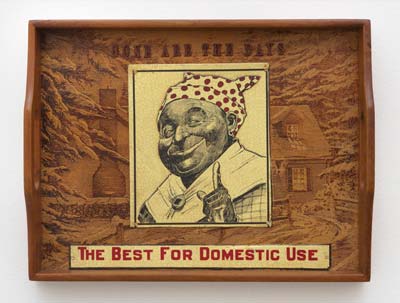

BETYE SAAR

GONE ARE THE DAYS (The Best for Domestic Use), 1999

Mixed media assemblage

11.5 x 15 x 2 inches

Betye Saar steps forward in time from slavery to address the post-emancipation period where African-Americans often performed service help in roles that were still limiting and still often held in low esteem. Maids and mammies in the home; boot blacks, porters and bellmen in industry. All of the work in this series are collages or assemblages constructed on serving trays using commonly found images from advertising (think Aunt Jemima and Uncle Ben), and various collectibles such as salt and pepper shakers, and embroidered dish clothes, depicting picaninnies, and other black stereotypes.

BETYE SAAR

WAITING TO SERVE, 2014

Mixed media assemblage

9.5 x 16 x 2.5 inches

Joyce Scott

NANNY NOW NIGGER LATER, 1989

Mixed media with leather and beads

17 x 5 x 6 inches

Collection of Greg Kucera and Larry Yocom

In the large body of "Mammy" figures made over the course of Joyce Scott's career, the artist suggests the tender protectiveness these black women held for their young white charges. In "Nanny Now, Nigger Later," the artist gives voice to the prejudice that can develop as a much loved young child grows into a deeply hateful adult. "Wet Nurse" depicts the women who suckle the newborns of other women, a role that many a black woman has played for their white mistresses or employers. The milk of life flowing from their black breasts into the mouths of their young white charges must seem an irony at some point in the lives of opposition these two forces may likely engage later..

Roger Shimomura

ROGER SHIMOMURA

BROADMOOR GARDENER, 2017

Acrylic on canvas

36 x 24 inches

SOLD

Roger Shimomura's autobiographical painting, "Broadmoor Gardeners," refers to his teenage years when he worked as a landscape gardener, often for the white families of more well-to-do high school classmates. He casts the action as in an Archie comic strip, but with his own image pushing a lawn mower, while anachronistically clothed in the traditional clothing for a low status worker from a Japanese ukiyo-e wood block print.

ROGER SHIMOMURA

LOCK HER UP, 2017

Acrylic on canvas

24 x 24 inches

$8,000

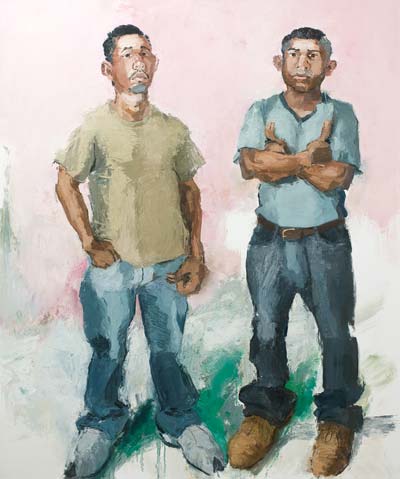

John Sonsini

JOHN SONSINI

SAUL & LORENZO, 2008

Oil on canvas

82 x 120 inches

Price on request

JOHN SONSINI

FRANCISCO & RAUL, 2009

Oil on canvas

72 x 60 inches

Price on request

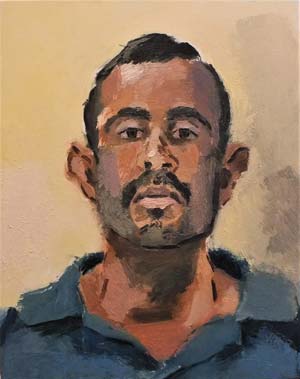

JOHN SONSINI

MIGUEL ANTONIO, 2017

Oil on canvas

72 x 48 inches

SOLD

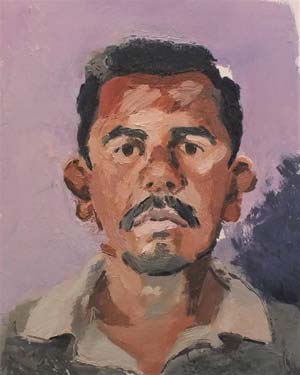

JOHN SONSINI

MIGUEL ANTONIO, 2017

Oil on canvas

20 x 16 inches

SOLD

JOHN SONSINI

LUIS, 2017

Oil on canvas

20 x 16 inches

$10,000

JOHN SONSINI

CHRISTIAN, 2016

Oil on canvas

20 x 16 inches

$10,000

John Sonsini's work, for more than forty years has dealt with Hispanic day laborers who are paid an hourly wage for performing various types of construction work. Instead of hiring these itinerant laborers from a nearby Home Depot to do yard work or construction, Sonsini began hiring them to pose for his paintings at a reasonable wage. In Sonsini's studio, the artist asks them, simply, to stand or sit still. And, to return five hours daily throughout the process of several days, until the painting is completed. In the intimate portrait, FRANCISCO & RAUL, the men stand silently looking back at the viewer, their expressions neutral, their clothing modest, their hands still. Some men take to the job easily, while others find it uncomfortable to be still rather than active.

Rodrigo Valenzuela

RODRIGO VALENZUELA

PROLE, 2015

HD digital video (screen shot shown here)

8 minutes 47 seconds

Edition of 5

RODRIGO VALENZUELA

MARIA TV, 2014

HD Video (screen shot shown here)

17 minutes 15 seconds

Edition of 5

Rodrigo Valenzuela's "MARIA TV" interweaves documentation of everyday activities of Latina domestic workers with reenactments of similar jobs as portrayed in soap operas and movies. The artist hired women who work as maids in Seattle hotels, and directed them in reenactments of their real-life roles. Using clips of various telenovelas as templates for the cast, the artist created a hybridized narrative in which the cast performs for the camera both as "as seen on TV" characters and as representing their own stories and lives.

Similarly, the cast of "Prole" are day workers, hired from the streets of Omaha when he was there on a residency award from the Bemis Foundation in 2015.

Kara Walker

KARA WALKER

PASTORAL, 1998

Wall painting in black, limited to 15 installations, with a signed and numbered certificate

72 x 80 inches

Edition of 15

SOLD

Kara Walker's "Pastoral" evokes the idea of a slave who must pretend to be something she isn't just to survive. A wolf in sheep's clothing is a concept that has many places in our culture, but the necessary desperation that slaves must have felt gives it a particular urgency. While still within her trademark imagery of the silhouette, this work is painted in black on a white wall through a large stencil, rather than as cut paper glued to a wall.

Lynne Yamamoto

LYNNE YAMAMOTO

RINGAROUNDAROSIE, 1997

Starched shirt sleeves, cigarette burns, pins

36 x 174 x 24 inches

$10,000

Lynne Yamamoto's grandmother was a private laundress working on a Hawaiian sugar plantation for the owners' family. Her installation of white male shirt sleeves suggests the demanding gestures of the male power structure in play on the plantation. Perhaps her revenge is indicated in the occasional cigarette burn in the fabric.

America has had a long history of getting its very hardest, least pleasant, and most dangerous work done by "the

other." Whether American citizens who survive at the lowest rungs of the economic ladder; or live precariously as

migrants or immigrants; or as slaves brought here against their will, there has always been a class of worker

forced to do work other Americans will not do.

Before the arrival of Europeans, the enslavement of war captives from one North American Indian tribe by another

was fairly common among certain native cultures. Beginning in the 15th century, (particularly in what would

become California), Native Americans were forced into labor by early explorers, soldiers and religious evangelists,

notably under the Jesuits. This situation grew successively worse for indigenous peoples as their fates passed

from the Spanish to the Mexican government in 1821, and then to the US Government in 1854.

As indentured servants arrived in the New World colonies in the first waves of European immigrants (mostly

British and Irish) in the 16th to 18th centuries, many American families depended on these non-family members to

raise their children and keep their households. In the 17th century, the steady stream of indentured servants from

all parts of Europe was also crucial to the tobacco plantations. Indentured servitude fell sharply with the American

Revolution, even as the African slave trade picked up steam. During the 16th to 19th centuries, over 12,000,000

Africans were brought to the Americas. Over 10,000,000 made it alive to this country, particularly to do the

gruesome work on sugar cane farms and the backbreaking toil on cotton plantations. After emancipation in 1863,

millions of former slaves were reduced to being share croppers-a life barely better than being actual slaves.

By the 19th and 20th centuries, cheap labor was introduced to the American work forces, notably in the railroad

industry, by laborers brought in-often illegally- from China, and elsewhere. Chinese immigrants and indentured

servants were denied any form of citizenship after 1882 and into the 1900s. American farms became more and

more dependent on the availability of unskilled laborers coming from Mexico and other central and south

American nations as the 20th century progressed. Now, in the 21st century, the bulk of Americans are no more

willing to do the grunt work and the low-wage work, leaving it to be done by those just coming to this country or

without the means to get better jobs. It becomes harder and harder to imagine that this country can ever function

without such labor forces.